Investing in Bonds

Bonds are a common investment for people targeting a low-risk investment portfolio. One of the pieces of advice I gave my kids (see others in this post) is to never buy anything you don’t understand. In this post, I’ll tell you what you need to know so you can decide whether investing in bonds is appropriate for you.

What is a Bond?

A bond is a loan you are giving the issuer. The parties to the transaction are exactly opposite of you taking out a loan. You’ll see the parallels if you compare the information in this post with that provided in my post on loans! When you buy a bond, you are the lender. The issuer of the bond is the borrower.

How Do Bonds Work?

The issuer of a bond sells the bonds to investors (i.e., lenders). Every bond has a face amount. Common face amounts are $100 and $1,000. The face value of the bond is called the par value. It is equivalent to the principal on a loan. When the issuer first sells the bonds, it receives the face amount for each bond.

The re-payment plan for a bond is different than for a loan. When you take out a loan, you make payments that include interest and a portion of your principal. Over the life of your loan, all of your payments are the same (unless the interest rate is adjustable). By comparison, a bond issuer’s payments include only the interest until the maturity date when it pays the final interest payment and returns the principal in full.

Before selling bonds, the issuer sets the coupon rate and the maturity date of the bond. The coupon rate is equivalent to the interest rate on a loan. The maturity date is the date on which the issuer will pay the par value to the owner of the bond. It can vary from something very short, like a year, all the way to 30 years. In Europe, there are even bonds with maturity dates in 99 years. In the meantime, the issuer will pay coupons (interest) equal to the product of the coupon rate and the par value, divided by the number of coupons issued per year.

Coupons are often issued quarterly. For example, if you owned a bond with a $1,000 par value, a 4% coupon rate and quarterly payments, you would get 1% of $1,000 or $10 a quarter in addition to the return of the par value on the maturity date.

What Price Will I Pay

You can buy bonds when they are first issued from the issuer or at a later date from other people who already own them. You can also sell bonds you own if you want the return of your initial investment before the bond matures. If you buy and sell bonds, the sale prices will be the market price of the bonds.

Present Value

Before explaining how the market value is calculated, I need to introduce the concept of a present value. A present value is the value today of a stated amount of money you receive in the future. It is calculated by dividing the stated amount of money by 1 + the interest rate adjusted for the length of time between the date the calculation is done and the date the payment will be received. Specifically, the present value at an interest rate of i of $X received in t years is:

The denominator of (1+i) is raised to the power of t to adjust for the time element.

Market Price = Present Value of Cash Flows

The market price of a bond is the present value of the future coupon payments and principal repayment at the interest rate at the time of the calculation is performed.

Interest Rate = Coupon Rate When Issued

The interest rate when the bond is issued is the coupon rate! Because the issuer sells the bonds at par value (the face amount of the bond), the par value has to equal the market value. For the math to work, the coupon rate must equal the interest rate at the time the bond is initially sold.

Interest Rates after Issuance

If interest rates change (more on that in a minute) after a bond is issued, the market value will change and become different from the par value because the “i” in the formula above will change. When the interest rate increases, the price of the bonds goes down and vice versa.

Also, as the bond gets closer to its maturity date, the exponent “t” in the formula will get smaller so it will have less impact on the present value, making the present value bigger. As such, all other things being equal, a bond that has a shorter time to maturity will have a higher market price than a bond that has a longer time to maturity. Remember that the par value is all paid at the end, so the market price formula is highly influenced by the present value of the repayment of the par value.

How is the Interest Rate Determined

There are two factors specific to an individual bond that influence the interest rate that underlies its price – the bond’s time to maturity and the issuer’s credit rating. In addition, there are broad market factors that influence the interest rates for all bonds. These factors influence the overall level of interest rates as well as the shape of the yield curve.

What is a Yield Curve

The interest rate on a bond depends on the time until it matures. If I look at the interest rates on US government bonds today (March 7, 2019) at this site, I see the following: The line on this graph is called a yield curve.

It represents the pattern of yields by maturity. In this case, there is some variation in yields up to 5 years and then the line goes up.

A “normal” yield curve would go up continuously all the way from the left to the right of the graph. Up to five years, the chart above would be considered essentially “flat” and, above five years, would be considered normal. If the entire yield curve went down, similar to what we see in the very short segment from one year to two years in this graph, it would be considered inverted.

Time to Maturity

The yield curve along with the maturity date of a bond influence the interest rate and therefore its market price. Looking at US Government bonds, the interest rates for bonds with maturities between 0 and 7 years are all around 2.5%.

The price of a 30-year bond will reflect interest rate of about 3%. If the yield curve didn’t change at all, the same 30-year bond would be priced using a 2.5% interest rate in 23 years (when it has 7 years until maturity). With the lower interest rate, the market value of the bond will increase (in addition to the increase in market value because the maturity date is closer).

Credit Rating

The other important factor that affects the price of a bond is its credit rating. Credit ratings work in the same manner as your credit score does. If you have a low credit score (see my post on credit scores for more information), you pay a higher interest rate when you take out a loan. The same thing happens to a bond issuer – it pays a higher interest rate if it has a low credit rating.Instead of having a numeric credit score, bonds are assigned letters as credit ratings. There are several companies that rate bonds, with Standard and Poors (S&P), Moodys and Fitch being the biggest three. When you buy a bond (more on that later), the credit rating for the bond will be quite clearly stated.

The graph below summarizes information I found on the website of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank (FRED).

It shows the interest rates on corporate bonds with different credit ratings on February 28, 2019. As you can see, there is very little difference in the interest rates of bonds rated AAA, AA and A, with a slightly higher interest rate for bonds rated BBB. Bonds with BBB ratings and higher are considered investment grade.Bonds with ratings lower than BBB are called less-than-investment grade, high yield or junk. You can see that the interest rates on bonds with less-than-investment grade ratings increase very rapidly, with C-rated bonds having interest rates close to 12%.

What are the Risks

There are two risks – default and market – that are inherent in bonds themselves and a third – inflation – related to using them as an investment.

Defaults

Default risk is the chance that the issuer will default or not make all of its coupon payments or not return the full par value when it is due. When an issuer defaults on a bond, it may pay the bond owner a portion of what is owed or it could pay nothing. The percentage of the amount owed that is not repaid is called the “loss given default.” If the loss given default is 100%, you lose the full amount of your investment in the bond, other than coupon payments you received before the default. At the other extreme, if the loss given default is only 10%, you would receive 90% of what is owed to you.Issuers of bonds with low credit ratings are considered riskier, meaning they are expected to have a higher chance that they will default than issuers with high credit ratings.

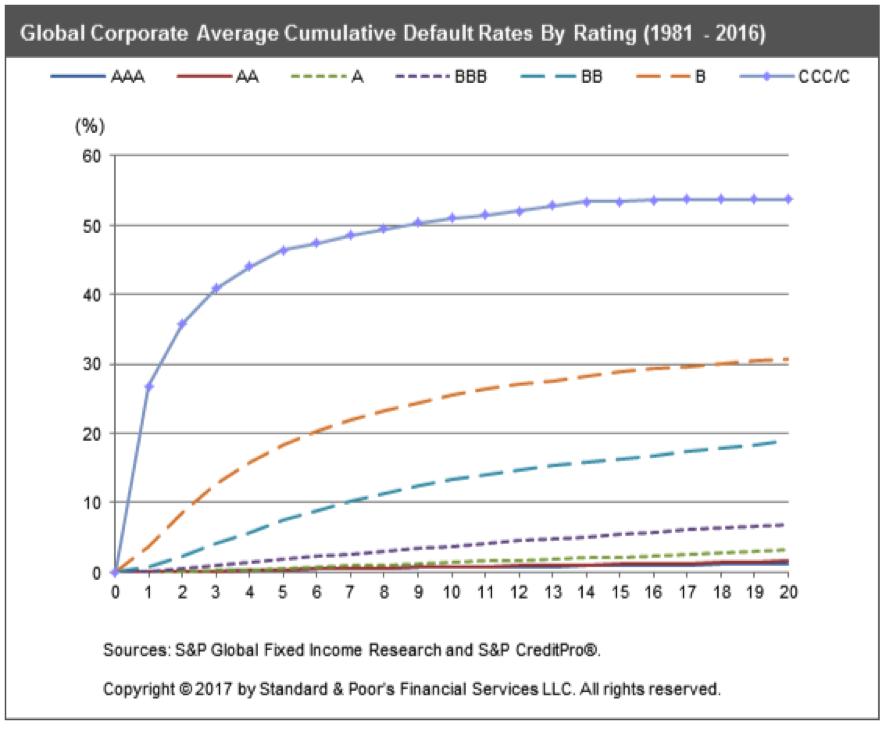

I always find this chart from S&P helpful in understanding default risk.

It shows two things – the probability of an issuer defaulting increases as the credit rating gets lower (e.g., the B line is higher than the A line) and the probability of default increases the longer the time until maturity.

These increases in the probability of default correspond to increases in risk. Recall from the previous section that interest rates increase as there is a longer time to maturity when the yield curve is normal and as the credit rating gets lower. The higher interest rates are compensation to the owner of the bond for the higher risk of default.

When you read the previous section and saw you could earn between just under 12% on a C-rated bond, you might have gotten interested. However, it has almost a 50% chance of defaulting in 7 years! The trade-off is that you’d have to be willing to take the risk that the issuer would have a 26% chance of defaulting in the first year and a 50% chance by the seventh year! It makes the 12% coupon rate look much less attractive.

Changes in Market Value

As I mentioned above, you can buy and sell bonds in the open market as an alternative to holding them to maturity. In either case, you will receive the coupon payments while you own the bond, as long as the issuer hasn’t defaulted on them. If you buy a bond with the intention of selling it before it matures, you have the risk that the market value will decrease between the time you purchase it and the time you sell it. Decreases in market values correspond to increases in interest rates. These increases can emanate from changes in the overall market for bonds or because the credit rating of the bond has deteriorated.

If you hold a bond to maturity and it doesn’t default, the amount you will get when it matures is always the principal. So, you can eliminate market risk if you hold a bond to maturity.

Interest Doesn’t Keep Up with Inflation

The third risk – inflation risk – is the risk that inflation rates will be higher than the total return on the bond. Let’s say you buy a bond with a $100 par value for $90, it matures in 5 years and the coupons are paid at 2%. Using the formulas above, I can determine that your total return (the 2% coupons plus the appreciation on the bond from $90 to $100 over 5 years) is 4.3%. You might have purchased this bond as part of your savings for a large purchase. If inflation caused the price of your large purchase to go up at 5% per year, you wouldn’t have enough money saved because your bond returned only 4.3%. Inflation risk exists for almost every type of invested asset you purchase if your purpose for investing is to accumulate enough money for a future purchase.

How are They Taxed

There are two components to the return you earn on a bond – the coupons and appreciation (the difference between what you paid for it and what you get when you sell it or it matures).

Tax on Coupons and Capital Gains

The coupons are considered as interest in the US tax calculation. Interest is included with your wages and many other sources of income in determining your taxes which have tax rates currently ranging from 10% to 37% depending on your income.

The difference between your purchase price and your sale price or the par value upon maturity is considered a capital gain. In the US, capital gains are taxed in a different manner from other income, with a lower rate applying for most people (0%, 15% or 20% depending on your total income and amount of capital gains).

States that have income taxes usually follow the same treatment with lower tax rates than the Federal government, but not always.

Some Bonds are Taxed Differently

Within this framework, though, not all bonds are treated the same. The description above applies to corporate bonds. Bonds issued by the US government are taxed by the Federal government but the returns are tax-free in most states.

Some bonds are issued by a state, municipality or related entity. The interest on these bonds is not taxed by the Federal government and is usually not taxed if you pay taxes in the same state that the issuer is located. Capital gains on these bonds are taxed in the same manner as corporate bonds.Included in this category of bonds are revenue bonds. Revenue bonds are issued by the same types of entities, but are for a specific project. They have higher credit risk than a bond issued by a state or municipality because they are backed by only the revenues from the project and not the issuer itself.

The manner in which a bond is taxed is important to your buying decision as it affects how much money you will keep for yourself after buying the bond. You should consult your broker or your tax advisor if you have any questions specific to your situation.

Do They Have Other Features

If you decide to buy bonds, there are some features you’ll want to understand or, at a minimum, avoid. Some of the types of bonds with these distinctive features are:

Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities or TIPS

TIPS are similar to US Government bonds except that the par value isn’t constant. The impact of inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index is determined between the issue date and the maturity date. If inflation over the life of the bond has been positive, the owner of the bond will be paid the original par value adjusted for the impact of inflation. If it has been negative, the owner receives the original par value. In this way, the owner’s inflation risk is reduced. It is completely eliminated if the owner purchased the bond to buy something whose value increases exactly with the Consumer Price Index.

Savings or EE Bonds

Savings bonds are a form of US Government bond. You can buy them with par values of as little as $25. They can be purchased for terms up to 30 years. Currently, savings bonds pay interest a 0.1% a year. The interest is compounded semi-annually and paid to the owner with the par value when the bond matures. With the currently very low interest rates, these bonds are very unattractive.

Zero-Coupon Bonds

The issuer of a zero-coupon bond does not make interest payments. Rather, when it issues the bond, the price is less than the par value. In fact, the price is the present value of just the principal payment. So, instead of paying the par value for a newly issued bond and getting coupon payments, the buyer pays a much lower price and gets the par value when the bond matures.

I don’t know all the details, but believe that, in the US, the owner needs to pay taxes on the appreciation in the value of the bond every year as if it were interest and not as a capital gain on sale. As such, it is better to own a zero-coupon bond in a tax-deferred or tax-free account, such as an IRA, a 401(k) or health savings account. I’ve owned one zero-coupon bond – it was my first investment in an IRA. If you want to buy a zero-coupon bond, I suggest talking to your broker or tax advisor to make sure you understand the tax ramifications.

Callable Bonds

A call is a financial instrument that gives one party the option to do something. In this case, the issuer of the bond is given the option to give you the par value earlier than the maturity date. When the issuer decides to exercise this option, the bond is said to be “called.” The bond contract includes information about when the bond is callable and under what terms. If you purchase a callable bond, you’ll want to understand those terms.Issuers are more likely to call a bond when interest rates have decreased. When interest rates go down, the issuer can sell new bonds at the lower interest rate and use the proceeds to re-pay the callable bond, thereby lowering its cost of debt.In a low-interest rate environment, such as exists today, a callable bond isn’t much different from a non-callable bond as it isn’t likely to get called. If interest rates were higher, a non-callable bond with the same or similar credit quality and coupon rate is a better choice than a callable bond. If the callable bond gets called, you will have cash that you now need to re-invest at a time when interest rates are lower than when you initially bought the bond. (Remember that the reason that callable bonds get called is that interest rates have gone down.)

Convertible Bonds

Convertible bonds allow the issuer to convert the bond to some form of stock. As will be explained below, stocks are riskier investments than bonds. If you buy a convertible bond, you’ll want to understand when and how the issuer can convert the bond and consider whether you are willing to own stock in the company instead of a bond.

How Does Investing in Bonds Differ from Other Investments

There are two other types of financial instruments that people consider buying as common alternatives to bonds – bond mutual funds and stocks. I’ll briefly explain the differences between owning a bond and each of these alternatives.

Bond Funds

There are two significant differences between owning a bond fund and own a bond.

A Bond Fund with the Same Quality Bonds Has Less Default Risk

If you own a bond fund, you are usually buying an ownership share in a pool containing a relatively large number of bonds. Owning more bonds increases your diversification (see this post for more on that topic). With bonds, the biggest benefit from diversification is that it reduces the impact of a single issuer defaulting on its payments. If you own one bond, the issuer defaults and the loss given default is 50%, you’ve lost 50% of your investment. If you own 100 bonds and one of them defaults with a 50% loss given default, you lose 0.5% of your investment.

A Bond Fund Has Higher Market Risk than Owning a Bond to Maturity

Recall that you eliminate market risk if you hold a bond until it matures. Almost all bond funds buy and sell bonds on a regular basis, so the value of the bond fund is always the market price of the bonds. Because the market price of bonds can fluctuate, owners of bond funds are subject to market risk. I cover the market risk of bond funds much more extensively in this post on the All Seasons portfolio.

Stocks

When you buy stock in a company, you have an ownership interest in the company. When you own a bond, you are a lender but have no ownership rights. To put these differences in perspective, owning a stock is like owning a share in vacation home along with other members of your extended family. By comparison, owning a bond is like being the bank that holds the mortgage on that vacation home.

Stocks Have More Market Risk

The market risk for stocks is much greater than for bonds. Ignoring defaults for the moment, the issuer has promised to re-pay you the par value of the bond plus the coupons, both of which are known and fixed amounts. With a stock, you are essentially buying a share of the future profits, whose amounts are very uncertain.

Stocks Have More Default Risk

The default risk for stocks is also greater than for bonds. When a company gets in financial difficulties, there is a fixed order in which people are paid what they are owed. Employees and vendors get highest priority, so get paid first. If there is money left over after paying all of the employees and vendors, then bondholders are re-paid. After all bondholders have been re-paid, any remaining funds are distributed among stockholders. Because stockholders take lower priority than bondholders, they are more likely to lose some or all of their investment if the company experiences severe financial difficulties or goes bankrupt.

Companies often issue bonds on a somewhat regular basis. When a bond is issued, it is assigned a certain seniority. This feature refers to the order in which the company will re-pay the bonds if it encounters financial difficulties. If you decide to invest in bonds of individual companies, especially less-than-investment grades bonds, you’ll want to understand the seniority of the particular bond you are buying because it will affect the level of default risk. Lower seniority bonds have lower credit ratings, so the credit rating will give you some insight regarding the seniority.

When is Investing in Bonds Right for Me

There isn’t a right or a wrong time to buy a bond, just as is the case with any other financial instrument. The most important thing about buying a bond is making sure you understand exactly what you are buying, how it fits in your investment strategy and its risks.

Low-Risk Investment Portfolio

If you are interested in a low risk investment portfolio, US Government and high-quality corporate bonds might be a good investment for you. As you think about this type of purchase, you’ll also want to think about the following considerations.

How Long until You Need the Money

If you are saving for a specific purchase, you could consider buying small positions in bonds of several different companies or US government bonds with maturities corresponding to when you need the money. If you’ll need the money in less than a year or two, you might be better off buying a certificate of deposit or putting the money in a money market or high yield savings account. If it is a long time until you’ll need the money and you think interest rates might go up, you’ll want to consider whether you can buy something with a maturity sooner than your target date without sacrificing too much yield so you can buy another bond in the future at a higher interest rate.

How Much Default Risk are You Willing to Take

If you aren’t willing to take any default risk, you’ll want to invest in US government bonds. If you are willing to take a little default risk, you can buy high-quality (e.g., AAA or AA) corporate bonds. You’ll want to buy small positions is a fairly large number of companies, though, to make sure you are diversified.

How Much Market Risk are You Willing to Take

If you are willing to take some market risk, you can more easily attain a diversified portfolio by investing in a bond mutual fund. As mentioned above, you’ll want to consider whether you think interest rates will go up or down during your investment horizon. If you think that are going to go up, there is a higher risk of market values going down than if you think they will be flat. In this situation, a bond fund becomes somewhat riskier than buying bonds to hold them to maturity. If you think interest rates are going to go down, there is more possible appreciation than if you think they will be flat.

High-Risk Investment Portfolio

If you want to make higher return and are willing to take more default risk, you can consider buying bonds of lower quality. As shown in the chart above, non-investment grade bonds pay coupons at very high interest rates. However, you need to recognize that you are taking on significantly more default risk. One approach for dabbling in high-yield bonds is to invest in a mutual fund that specializes in those securities. In that way, you are relying on the fund manager to decide which high-yield bonds have less default risk. You’ll also get much more diversification than you can get on your own unless you have a lot of time and money to invest in the bonds of a large number of companies.

Where Do I Buy Bonds and Bond Funds

You can buy individual bonds and bond mutual funds at any brokerage firm. Many banks, particularly large ones, have brokerage divisions, so you can often buy bonds at a bank. This article by Invested Wallet provides details on how to open an account at a brokerage firm.All US Government bonds, including Savings Bonds and TIPS can be purchased at Treasury Direct, a service of the US Treasury department. You’ll need to enter your or, if the bond is a gift, the recipient’s social security number and both you and, if applicable, the recipient need to have accounts with Treasury Direct. US Savings Bonds can be bought only through Treasury Direct. You can buy all other types of government bonds at any brokerage firm, as well.

As discussed in this post, it is best to buy bonds in a tax-advantaged account, such as an IRA, 401(k), Tax-Free Savings Account (TFSA) or Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP) than a taxable account. You pay tax on the coupons every year when bonds are held in a taxable account, but you get the benefit of compounding without paying taxes along the way in a tax-advantaged account.