Tax-Efficient Investing Strategies - USA

You can increase your savings through tax-efficient investing. Tax-efficient investing is the process of maximizing your after-tax investment returns by buying your invested assets in the “best” account from a tax perspective. You may have savings in a taxable account and/or in one or more types of tax-sheltered retirement accounts. Your investment returns are taxed differently depending on the type of account in which you hold your invested assets. In this post, I’ll provide a quick overview of the taxes applicable to each type of account (since I cover taxes on retirement plans in much greater detail in this post) and provide guidelines for how to invest tax-efficiently. To test out some of the strategies discussed here, check out the last calculator in this post.

The strategy for tax-efficient investing differs from one country to the next due to differences in tax laws so I’ll talk about tax-efficient investing strategies in the US in this post and in Canada in this post.

Types of Investment Returns

I will look at four different types of investments:

Individual stocks with high dividends

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs)

I will not look at individual stocks with little or no dividends. The returns on those stocks are essentially the same as the returns on ETFs and are taxed in the same manner.

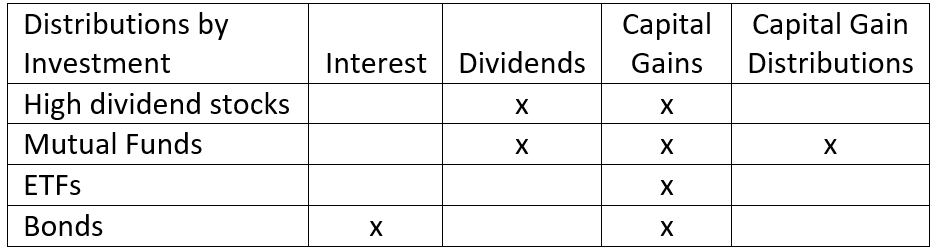

The table below shows the different types of returns on each of these investments.

Cash Distributions

Interest and dividends are cash payments that the issuers of the financial instrument (i.e., stock, fund or bond) make to owners.

Capital Gains

Capital gains come from changes in the value of your investment. You pay taxes on capital gains only when you sell the financial instrument which then makes them realized capital gains. The taxable amount of the realized capital gain is the difference between the amount you receive when you sell the financial instrument and the amount you paid for it when you bought it. Unrealized capital gains are changes in the value of any investment you haven’t yet sold. If the value of an investment is less than what you paid for it, you are said to have a capital loss which can be thought of as a negative capital gain.

Mutual Funds

Mutual funds are a bit different from stocks and ETFs. They can have the following types of taxable returns.

Dividends – A mutual fund dividend is a distribution of some or all of the dividends that the mutual fund manager has received from the issuers of the securities owned by the mutual fund.

Capital gain distributions – Capital gain distributions are money the mutual fund manager pays to owners when a mutual fund sells some of its assets.

Capital gains – As with other financial instruments, you pay tax on the any realized capital gains (the difference between the amount you receive when you sell a mutual fund and the amount you paid for it) when you sell a mutual fund.

Tax Rates

The four types of distributions are taxed differently depending on the type of account in which they are held – Taxable, Roth or Traditional. 401(k)s and Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) are forms of retirement accounts that can be either Roth or Traditional accounts and are discussed in more detail in in this post.

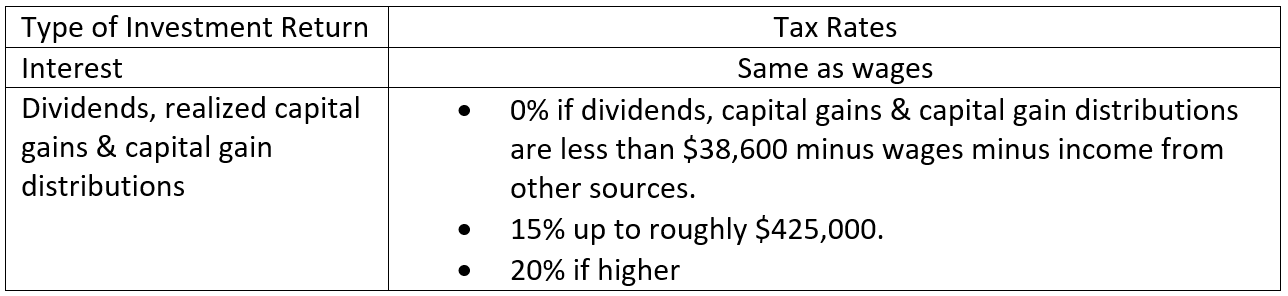

Accounts other than Retirement Accounts

I’ll refer to accounts that aren't retirement accounts as taxable accounts. You pay taxes every year on dividends and realized capital gains in a taxable account, whereas you pay them either when you contribute to or make a withdrawal from a retirement account. The table below shows how the different types of investment returns are taxed when they are earned in a taxable account.

For many employed US residents (i.e., individuals with taxable income between $38,700 and $157,500 and couple with taxable income between $77,400 and $315,000 in 2018), their marginal Federal tax rate wages and therefore on interest is likely to be 22% or 24%.

In a taxable account, you pay taxes on investment returns when you receive them. You are considered to have received capital gains when you sell the financial instrument.

Roth Retirement Accounts

Before you put money into a Roth account, you pay taxes on it. Once it has been put into the Roth account, you pay no more income taxes regardless of the type of investment return unless you withdraw the investment returns before you attain age 59.5 in which case there is a penalty. As such, the tax rate on all investment returns held in a Roth account is 0%.

Traditional Retirement Accounts

You pay income taxes on the total amount of your withdrawal from a Traditional retirement account at your ordinary income tax rate. Between the time you make a contribution and withdraw the money, you don’t pay any income taxes on your investment returns.

After-Tax Returns by Type of Account

To illustrate the differences in how taxes apply to each of these four financial instruments, I’ll look at how much you would have if you have $1,000 to invest in each type of account at the end of one year and the end of 10 years.

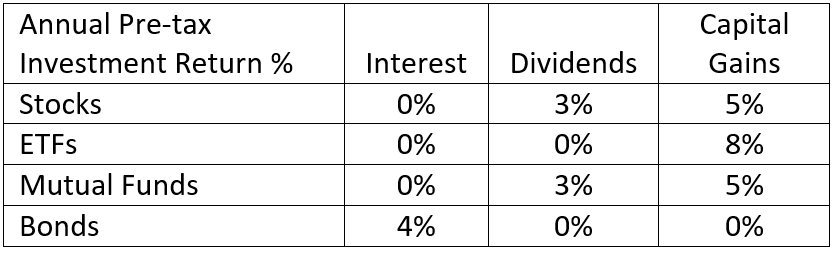

Here are the assumptions I made regarding pre-tax investment returns.

Mutual funds usually distribute some or all of realized capital gains to owners. That is, if you own a mutual fund, you are likely to get receive cash from the mutual fund manager related to realized capital gains in the form of capital gain distributions. Whenever those distributions are made, you pay tax on them. For this illustration, I’ve assumed that the mutual fund manager distributes all capital gains to owners, so they are taxed every year.

Here are the tax rates I used for this illustration.

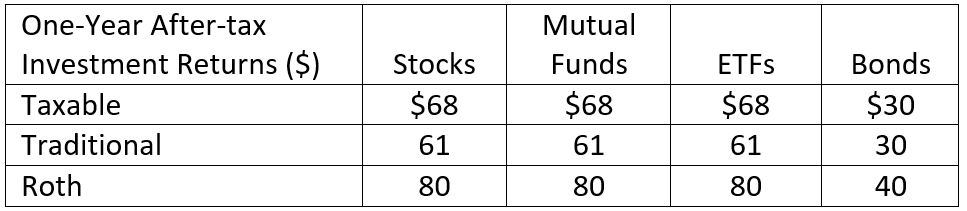

One-Year Investment Period

Let’s say you have $1,000 in each account. I assume you pay taxes at the end of the year on the investment returns in your Taxable account. If you put the money in a Traditional account, I assume that you withdraw all of your money and pay taxes at the end of the year on the entire amount at your ordinary income tax rate. (I’ve assumed you are old enough that you don’t have to pay a penalty on withdrawals without penalty from the retirement accounts.)

The table below shows your after-tax investment returns after one year from your initial $1,000. Note that the pre-tax returns are the same as the returns in the Roth row, as you don’t pay income taxes on returns you earn in your Roth account.

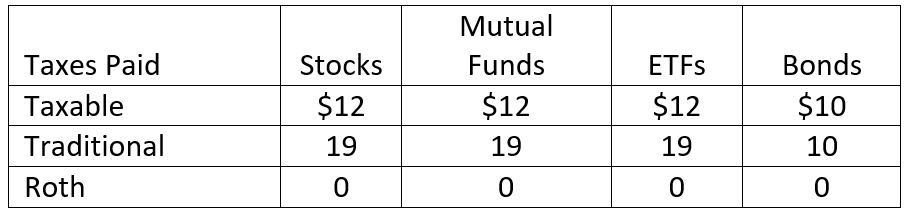

The table below shows the taxes you paid on your returns during that year.

When looking at these charts, remember that you paid income taxes on the money you contributed to your Taxable and Roth accounts and that those taxes are not considered in these comparisons. This post focuses on only the taxes you pay on your investment returns.

Comparison of Different Financial Instruments in Each Type of Account

Looking across the rows, you can see that, for each type of account, stocks, mutual funds and ETFs have the same one-year returns and tax payments. In this illustration, all three of stocks, mutual funds and ETFs have a total return of 8%. It is just the mix between appreciation, capital gain distributions and dividends that varies. The tax rates applicable to dividends and capital gains are the same so there is no impact on the after-tax return in a one-year scenario.

In all accounts, bonds have a lower after-tax return than any of the other three investments. Recall, though, that bonds generally provide a lower return on investment than stocks because they are less risky.

Comparison of Each Financial Instrument in Different Types of Accounts

Looking down the columns, you can see the impact of the differences in tax rates by type of account for each financial instrument. You have more savings at the end of the year if you invest in a Roth account than if you invest in either of the other two accounts for each type of investment. Recall that you don't pay any taxes on returns on investments in a Roth account.

The returns on a taxable account are slightly higher than on a Traditional account for stocks, mutual funds and ETFs. You pay taxes on the returns in a taxable account at their respective tax rates – usually 15% in the US for dividends and capital gains. However, you pay taxes on Traditional account withdrawals at your ordinary income tax rate – assumed to be 24%. Because the ordinary income tax rates are higher than the dividend and capital gain tax rates, you have a higher after-tax return if you invest in a taxable account than a Traditional account for one year. For bonds, the taxes and after-tax returns are the same in a Traditional and taxable account because you pay taxes on interest income in taxable accounts and distributions from Traditional accounts at your marginal ordinary income tax rate.

Remember, though, that you had to pay income taxes on the money you put into your taxable account before you made the contribution, whereas you didn’t pay income taxes on the money before you put it into your Traditional retirement account.

Ten-Year Investment Period

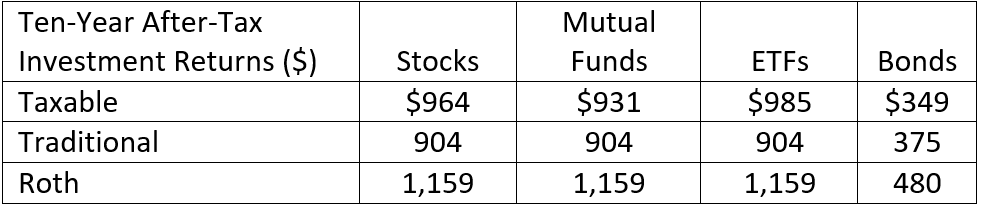

I’ve used the same assumptions in the 10-year table below, with the exception that I’ve assumed that you will pay ordinary income taxes at a lower rate in 10 years because you will have retired by then. I’ve assumed that your marginal tax rate on ordinary income in retirement will be 22%.

Comparison of Different Financial Instruments in Each Type of Account

If you look across the rows, you see that you end up with the same amount of savings by owning any of stocks, mutual funds and ETFs if you put them in either of the retirement account. The mix between capital gains, capital gain distributions and dividends doesn’t impact taxes paid in a tax-sheltered account, whereas it makes a big difference in taxable accounts, as can be seen by looking in the Taxable row.In taxable accounts, ETFs provide the highest after-tax return because they don’t have any taxable transactions until you sell them. I have assumed that the stocks pay dividends every year. You have to pay taxes on the dividends before you can reinvest them, thereby reducing your overall savings as compared to an ETF. You have to pay taxes on both dividends and capital gain distributions from mutual funds before you can reinvest those proceeds, so they provide the least amount of savings of the three stock-like financial instruments in a taxable account.

Comparison of Each Financial Instrument in Different Types of Accounts

Looking down the columns, we can compare your ending savings after 10 years from each financial instrument by type of account. You earn the highest after-tax return for every financial instrument if it is held in a Roth account, as you don’t pay any taxes on the returns.

For bonds, you earn a higher after-tax return in a Traditional account than in a taxable account. The tax rate on interest is about the same as the tax rate on Traditional account withdrawals. When you hold a bond in a taxable account, you have to pay income taxes every year on the coupons you earn before you can reinvest them. In a Traditional account, you don’t pay tax until you withdraw the money, so you get the benefit of interest compounding (discussed in this post) before taxes.

Your after-tax return is higher in a taxable account than in a Traditional account for the three stock-like investments. The lower tax rate on dividends and capital gains in the taxable account, even capital gain distributions, more than offsets the fact that you have to pay taxes on dividends and mutual fund capital gain distributions before you reinvest them.

Illustration of Tax Deferral Benefit

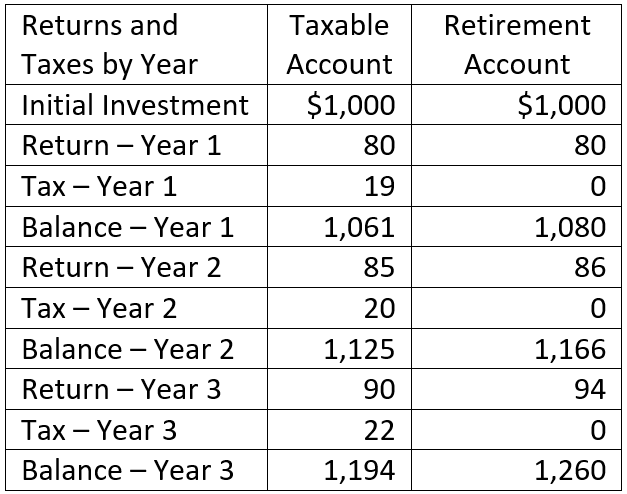

The ability to compound your investment returns on a tax-deferred basis is an important one, so I’ll provide an illustration. To keep the illustration simple, let’s assume you have an asset that has a taxable return of 8% every year and that your tax rate is constant at 24% (regardless of the type of account).

The table below shows what happens over a three-year period.

By paying taxes in each year, you reduce the amount you have available to invest in subsequent years so you have less return.

The total return earned in the taxable account over three years is $255; in the tax-deferred account, $260. The total of the taxes for the taxable account is $61. Multiplying the $260 of return in the tax-deferred account by the 24% tax rate gives us $62 of taxes from that account. As such, the after-tax returns after three years are $194 in the taxable account and $197 in the tax-deferred account.

These differences might not seem very large, but they continue to compound the longer you hold your investments. For example, after 10 years, your after-tax returns on the tax-deferred account, using the above assumptions, would be almost 10% higher than on the taxable account.

Tax-Efficient Investing for Portfolios

It is great to know that you get to keep the highest amount of your investment returns if you hold your financial instruments in a Roth. However, there are limits on how much you can put in Roth accounts each year. Also, many employers offer only a Traditional 401(k) option. As a result, you may have savings that are currently invested in more than one of Roth, Traditional or taxable accounts. You therefore will need to buy financial instruments in all three accounts, not just in a Roth.

Here are some guidelines that will help you figure out which financial instruments to buy in each account:

You’ll maximize your after-tax return if you buy your highest yielding financial instruments in your Roth. Because they generate the highest returns, you will pay the most taxes on them if you hold them in a taxable or Traditional account.

Keep buying your high-yielding financial instruments in descending order of total return in your Roth accounts until you have invested all of the money in your Roth accounts.

If two of your financial instruments have the same expected total return, but one has higher annual distributions (such as the mutual fund as compared to the stocks in the example above), you’ll maximize your after-tax return if you put the one with the higher annual distributions in your Roth account.

Once you have invested all of the money in your Roth account, you’ll want to invest your next highest yielding financial instruments in your Taxable account.

You’ll want to hold your lower return, higher distribution financial instruments, such as bonds or mutual funds, in your Traditional account. There is a benefit to holding bonds in a Traditional account as compared to a taxable account. The same tax rates apply to both accounts, but you don’t have to pay taxes until you withdraw the money from your Traditional account, whereas you pay them annually in your taxable account. That is, you get the benefit of pre-tax compounding of the interest in your Traditional account.

Applying the Guidelines to Two Portfolios

Let’s see how to apply these guidelines in practice using a couple of examples. To make the examples a bit more interesting, I’ve increased the annual appreciation on the ETF to 10% from 8%, assuming it is a higher risk/higher return type of ETF than the one discussed above. All of the other returns and tax assumptions are the same as in the table earlier in this post.

Portfolio Example 1

In the first example, you have $10,000 in each of a taxable account, a Traditional account and a Roth account. You’ve decided that you want to invest equally in stocks, mutual funds and ETFs.You will put your highest yielding investment – the ETFs, in your Roth account. The stocks and mutual fund have the same total return, but the mutual fund has more taxable distributions every year. Therefore, you put your mutual funds in your Traditional account and your stocks in your taxable account.

Portfolio Example 2

In the second example, you again have $10,000 in each of a taxable account, a Traditional account and a Roth account. In this example, you want to invest $15,000 in the high-yielding ETFs but offset the risk of that increased investment by buying $5,000 in bonds. You’ll split the remaining $10,000 evenly between stocks and mutual funds.

First, you buy as much of your ETFs as you can in your Roth account. Then, you put the remainder in your taxable account, as the tax rate on the higher return from the ETFs is lower in your taxable account (the 15% capital gains rate) than your Traditional account (your ordinary income tax rate). Next, you put your low-yielding bonds in your Traditional account. You now have $5,000 left to invest in each of your taxable and Traditional accounts. You will invest in mutual funds in your Traditional account, as you don’t want to pay taxes on the capital gain distributions every year if they were in your taxable account. That means your stocks will go in your taxable account.

Risk

There is a very important factor I’ve ignored in all of the above discussion – RISK (a topic I cover in great detail in this post). The investment returns I used above are all risky. That is, you won’t earn 3% dividends and 5% appreciation every year on the stocks or mutual funds or 10% on the ETFs. Those may be the long-term averages for the particular financial instruments I’ve used in the illustration, but you will earn a different percentage every year.

If your time horizon is short, say less than five to ten years, you’ll want to consider the chance that one or more of your financial instruments will lose value over that time frame. With perfect foresight, you would put your money-losing investments in your Traditional account because you would reduce the portion of your taxable income taxed at the higher ordinary income tax by the amount of the loss when you withdraw the money. Just as the government gets a share of your profits, it also shares in your losses.

The caution is that financial instruments with higher returns also tend to be riskier. If, in the US, you put your highest return investments – the ETFs in my example – in your Roth account, their value might decrease over a short time horizon. In that case, your after-tax loss is the full amount of the loss. If, instead, you had put that financial instrument in your Traditional account, the government would share 24% (your marginal ordinary tax rate) of the loss in my example.

In conclusion, if you plan to allocate your investments using the above guidelines, be sure to adjust them if your time horizon is shorter than about 10 years to minimize the chance that you will have to keep all of a loss on any one financial instrument.